Imagine a teacher being able to see exactly what a student was thinking. The idea is as outlandish as it is profound. For those philosophically inclined, it might evoke the concept of mind–body dualism, formulated by philosopher and mathematician René Descartes in the 1600s, which posits that while the body is physical and observable, thoughts exist in another realm entirely—invisible and known only from within.

This fundamental limitation can make it difficult to understand what is happening in students’ minds during the learning process. Teachers are often left to guess. But there are ways to get closer to “seeing” students’ thoughts. Thinking routines for math are designed to make thought processes visible to both teachers and students. They provide a window into students’ reasoning and sense making and help learners develop the key skills of observation, questioning, and reflection.

What are thinking routines for math?

Researchers at the Harvard Graduate School of Education’s Project Zero have made a number of important contributions to the field of education, with one of the best known being a set of practices called thinking routines.

Broadly speaking, a classroom routine is a predictable sequence of steps that helps students know what to expect and how to engage in learning. Thinking routines are routines with a special focus—to make thinking visible. They occur as brief mini-strategies that are easy to learn and help students both learn content more deeply and cultivate their thinking. According to Project Zero, “Thinking routines invite learners of any age to be close observers, organize their ideas, to reason carefully, and to reflect on how they are making sense of things.”

Much of learning math involves solving problems and making sense of abstract concepts, so students benefit from regular structures for thinking, writing, and talking about math. Thinking routines help students focus on making sense of mathematical ideas rather than simply producing correct answers. The routines provide scaffolds for students to ask thoughtful questions, explain their reasoning, and make connections.

Project Zero has organized many thinking routines with a wide variety of applications. Several are known as core routines—meaning they are simple, applicable across content areas and age groups, and can be used at multiple points of learning. Below are a few routines that can work in a math classroom. These all happen to follow a clear three-step sequence, although thinking routines in general can take a variety of formats and require different levels of facilitation from the teacher.

- Connect, Extend, Challenge: This routine has students answering three questions about a new concept: one about how it connects to a concept they already know, one about how it extends their thinking, and one about what they find challenging. This routine helps students make connections between new ideas and prior knowledge. It also encourages them to take stock of ongoing questions and difficulties as they reflect on what they are learning.

- See, Think, Wonder: This routine involves three questions that rely on close observation: What do you see? What do you think about that? What does it make you wonder? These questions encourage students to make careful observations and thoughtful interpretations and help to stimulate curiosity and inquiry.

- Think, Puzzle, Explore: This routine presents students with three questions that work well at the start of a new topic: one asking what they think, one asking what puzzles them, and one asking what they want to explore. This series of questions activates prior knowledge, generates ideas and curiosity, and sets the stage for deeper inquiry.

Thinking routines invite learners of any age to be close observers, organize their ideas, to reason carefully, and to reflect on how they are making sense of things.

Thinking routines, Thinking Classrooms, and other terms

Before we dive deeper into thinking routines for math, let’s clarify a few terms. “Thinking routines” fit alongside efforts large and small and across all grades to study how students can cultivate thinking and how teachers can facilitate it and see evidence of it. Thinking routines are in fact part of a larger project called Visible Thinking that generally aims to illuminate student thinking. And this isn’t to be confused with Visible Learning, an influential corpus of books and research that build on a 2009 meta-study synthesizing findings across over 50,000 studies and over 80 million students worldwide.

Another similar term gaining in popularity is Building Thinking Classrooms, an educational approach developed by Dr. Peter Liljedahl, a researcher at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, Canada. Like thinking routines, the goal of Thinking Classrooms is to help students become active participants in their own learning. But thinking routines are individual strategies that make student thinking visible, whereas Thinking Classrooms can involve transforming the entire classroom environment, from the furniture arrangement to grouping decisions and assessment practices.

Visible thinking routines for math

As mentioned earlier, thinking routines are part of a larger research-based framework developed by Project Zero known as Visible Thinking. The goal of Visible Thinking is to make students’ thinking visible to themselves, their peers, and their teachers to guide reasoning, sense making and encourage active processing. Thinking routines are one of the primary tools for Visible Thinking, as they help to externalize the mental steps students take when working through problems.

When thinking becomes visible, teachers can identify misconceptions early and guide discussion appropriately. Students gain insight into their own thought processes and learn from others. These benefits have extra urgency in math, where students may seek prescribed steps to follow instead of looking to a understand a concept more deeply. Thinking routines might also help to identify negative thoughts about math in general, something many children (and adults) feel that can hinder math development.

Why math thinking routines matter

Math thinking routines shift the focus from finding the right answer to deeply engaging in the problem-solving process. They help students develop habits that enable them to understand their own thinking and explain it to others. In the process of using them, teachers can more easily compare students’ knowledge with the knowledge being taught.

Thinking routines are especially important in the math classroom because they help students make connections that deepen their conceptual understanding and uncover the ideas behind the procedures they are learning to use, which supports the development of procedural fluency as well. Instead of memorizing steps for a specific situation, students see the bigger picture of which the steps are a part.

By encouraging students to wonder and explore, thinking routines invite creativity and curiosity in a subject often associated with rigidity, allowing for deeper engagement and learning. Thinking routines also help to support students’ mathematical identity. As students become comfortable and confident in describing the ways they think about math, they can learn to see themselves as a “math person,” i.e., someone who is unafraid of drawing on mathematical knowledge to solve problems.

How do thinking routines extend traditional math instruction?

Using thinking routines is by no means the opposite of delivering “traditional” math instruction. This often refers to a style of teaching focused on lecturing to the whole class at once, or the “sage on the stage,” as popularized after Alison King’s influential 1993 research article. There, King contrasts it with a “guide on the side,” referring to a constructivist style of teaching where teachers guide students in solving problems more independently. “Traditional” instruction is sometimes also used to describe the opposite of other styles of teaching, such as inquiry-based learning or a flipped classroom. All classrooms are different, of course, and even “traditional” setups are likely to incorporate “non-traditional” strategies such as math centers or group projects to help students refine their thinking and solve complex math problems.

No matter how one thinks about traditional math instruction, thinking routines can fit into them. Thinking routines are, in general, a way to extend traditional math instruction. They support explicit instruction and skills practice by helping students make their thinking visible. They also create structured opportunities for students to explain the ideas they have in the course of solving problems. During thinking routines, the teacher becomes more of a “guide on the side,” helping students to work through their thinking.

Examples of thinking routines used with math lessons

The following examples show how thinking routines can be used to deepen students’ mathematical reasoning, sense making, and reflection. Students can record their responses in math notebooks or on sticky notes, then share ideas with a partner or small group. Consider showing a few examples to the whole class to launch discussion and highlight different patterns in student thinking.

Using Connect, Extend, Challenge in a rounding lesson

This routine works well after students have experienced something new. Here’s an example of how it could play out shortly after facilitating instruction on how to round numbers to the nearest ten or hundred:

Connect: How does rounding connect to something you already know?

This connects to when we put numbers on a number line. Rounding is like deciding which ten or hundred a number is closest to.

Extend: What new ideas have you learned?

I learned that the halfway point helps me know whether to round up or down.

Challenge: What’s still confusing or what new questions do you have about rounding?

I’m still wondering what to do when a number is exactly in the middle.

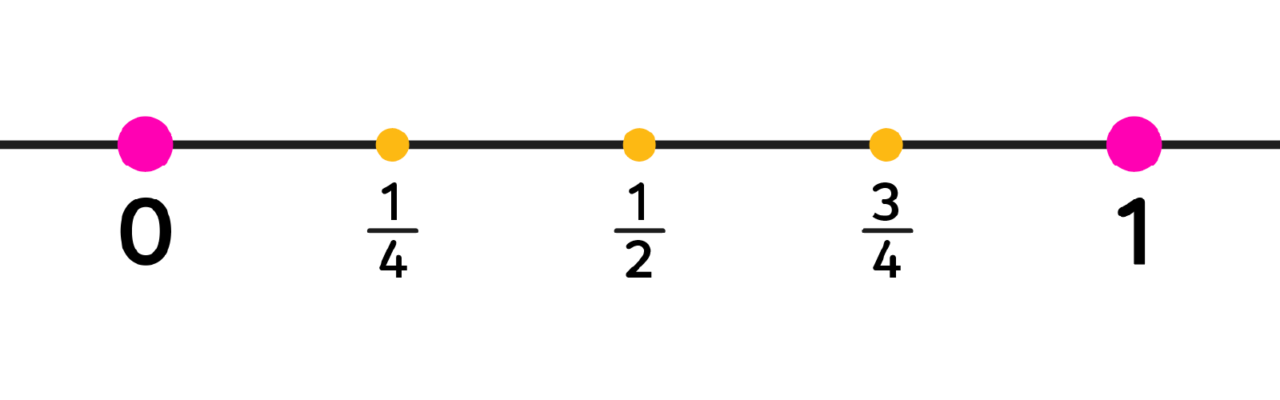

Using See, Think, Wonder in a lesson on fractions on a number line

This routine can be useful when you want to help students make sense of highly visual lessons, such as placing numbers along a number line. After students experience a number line from 0 to 1 with the fractions ¼, ½, and ¾ noted, use See, Think, Wonder to help them move from noticing positions to reasoning about numerical relationships. For example:

See: What do you notice on the number line?

I see 0 on the left and 1 on the right. I see ½ in the middle. I see ¼ halfway between 0 and ½ , and I see ¾ halfway between ½ and 1.

Think: What do you think is true about these fractions?

I think ½ is bigger than ¼ and smaller than ¾.

Wonder: What questions or puzzles do you have about these fractions?

I wonder what fractions would go between ¾ and 1.

Using Think, Puzzle, Explore in a linear functions lesson

This routine helps students take stock of what they already know and identify questions to ask next. When exploring the concept of linear functions, you can use the Think, Puzzle, Explore routine to spark inquiry. For example:

Think: What do you think you already know about how changing a line’s slope affects its graph?

I think if the slope is steeper, the line goes up faster.

Puzzle: What questions or puzzles do you have about slope?

I’m puzzled by what happens when the slope is negative or zero. How does that change the line?

Explore: What would you like to explore further to test your thinking or answer your questions?

I want to explore whether changing the slope changes the x-intercept too.

Bringing daily math thinking routines into your classroom

Incorporating math thinking routines in your instruction doesn’t have to happen all at once. To start, consider choosing just one routine to use consistently. Once students become familiar with the process, you can embed other routines at natural points in your lessons, such as before introducing a new concept to spark curiosity, during problem-solving to encourage observation, or after a lesson to prompt reflection. Keep prompts visible on the board and model your own thinking aloud to show what it looks like. Ask students to share their thoughts verbally or in writing and make time for discussion.

Routines and guidance to promote curiosity, observation, and reflection can be found throughout HMH’s math programs. Into Math includes Spark Your Learning activities at the beginning of each lesson that are designed to pique students’ curiosity and develop conceptual understanding through a student-centered approach.

Thinking in math

Thinking routines offer a research-based method for helping students examine and discuss their own thinking. When thinking routines become part of an overall classroom culture that seeks to make thinking visible, learners move beyond memorizing steps and procedures to building habits of reasoning, with benefits that extend far beyond the math classroom.

***

HMH’s core math solution Into Math for Grades K–Algebra 1 includes a variety of routines, real-world connections, and problem-solving strategies that deepen students’ mathematical understanding.

Teach the fun of math with five hands-on activities that spark curiosity in your students.