If you’ve been in any professional development or curriculum meeting lately, you’ve probably heard a lot about the science of reading and structured literacy. Maybe you’ve even wondered: Are they the same thing?

You’re not alone! These terms are related, but not interchangeable. Understanding the difference can make a huge impact on your students’ reading success.

The “science of reading” movement has transformed how educators think about reading instruction. Across the country, schools are investing in curriculum and professional learning aligned to findings in the science of reading research to ensure that all students have ongoing, effective, evidence-based literacy instruction.

The movement has introduced another important term, structured literacy; sometimes, the distinction between the two can be confusing. Both are essential to results-oriented literacy instruction, but they play different roles in helping students build the skills they need to become fluent readers.

Understanding the components of structured literacy supports educators’ understanding of how students learn to read and reading instruction. It’s not about a single program or textbook: it is about teaching grounded in theory and evidence, intentional assessment and instructional design, and the understanding of how children learn to read.

Structured literacy vs. the science of reading

The science of reading refers to the vast body of interdisciplinary research explaining how the human brain learns to read. Drawing from research conducted in cognitive psychology, linguistics, and neuroscience, this collective body of knowledge identifies the processes that allow readers to decode, comprehend, and internalize written language.

Structured literacy, by contrast, is the application of that research in instruction and is supported by the International Dyslexia Association (IDA). Structured literacy translates decades of scientific findings into day-to-day teaching practices. So, while the science of reading provides the “why,” structured literacy delivers the “how.”

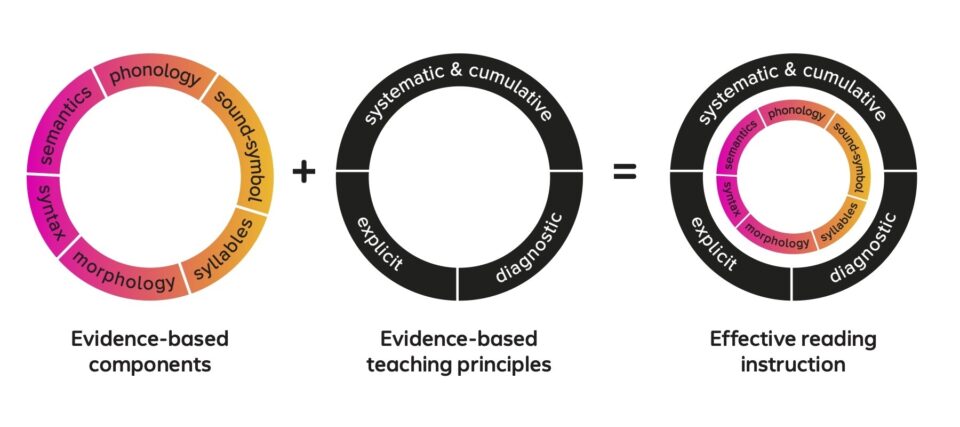

High-quality curriculum and professional learning puts science of reading research into practice while deepening teachers’ understanding. Ultimately, the goal is to ensure instruction is grounded in these principles of structured literacy:

- Explicit: Concepts are directly taught, not left for students to infer.

- Systematic and cumulative: Instruction follows a planned, logical progression, and each skill builds on previously taught knowledge.

- Diagnostic: Instruction is responsive, individualized, and data-driven, based on formal and informal assessment.

These principles ensure that every student receives instruction that supports mastery of foundational reading skills like decoding, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension.

The 6 components of structured literacy

Structured literacy instruction integrates six components. Each one builds upon and reinforces the others, creating a comprehensive approach to reading instruction.

1. Phonology

Phonology is the study of the sound system of language. Phonology helps students develop phonemic awareness—the ability to notice, think about, and work with the individual sounds (phonemes) in spoken words.

Phonology is critical because students who struggle to perceive and work with sounds in words often have difficulty learning to read. Blending and segmenting phonemes, rhyming, and manipulating sounds (e.g., changing /m/ in mat to /s/ to make sat) lay the foundation for decoding and spelling.

2. Sound-symbol correspondence

Once students can hear and identify sounds, they need to learn how those sounds connect to letters and letter combinations, or graphemes. This sound–symbol correspondence is phonics.

Through systematic phonics instruction, students learn the predictable relationships between sounds and letters, giving them the tools to decode new words. Teaching these correspondences explicitly and in a cumulative sequence ensures students master one set of patterns before moving to the next.

Phonics is a cornerstone of foundational reading skills. When anchored in structured literacy, it becomes a living reading experience that is far more useful and interesting than memorizing rules. It helps form a reader’s system of logic that empowers them to read any word they encounter—both words they already know and new words

3. Syllable instruction

Understanding syllable types helps students decode longer and more complex words. English syllables come in six primary types: closed, open, vowel-consonant-e, vowel team, r-controlled, and consonant-le. Luckily for us, each type follows a predictable pattern.

When students learn to identify these patterns and how to use them to deconstruct words, they can tackle multisyllabic words with accuracy and confidence. This knowledge supports fluency, comprehension, and spelling.

4. Morphology

Morphology is the study of morphemes, the smallest units of meaning in language, also known as roots, prefixes, and suffixes. Teaching morphology enhances vocabulary, comprehension, and spelling.

For example, teaching students that “bio” means “life” gives them a clue to the meaning of words like biology, biography, and biodegradable, especially when combined with knowledge of other morphemes. Morphological instruction also supports students as they advance through the grades and into secondary school, where they encounter more multisyllabic words.

5. Syntax

Syntax, the formation of sentences and their associated grammatical rules, and the relationship between words and phrases in a sentence, helps readers understand how sentences work. When the knowledge is applied to text, the reader is equipped to understand what sentences mean. If comprehension is the destination, syntax is the roadmap. Syntax instruction helps students recognize parts of speech, sentence types, and punctuation patterns.

When students understand syntax, they can read and write sentences that are coherent and grammatical. It also improves comprehension: Recognizing the difference between “The boy chased the car” and “The car chased the boy” is entirely dependent on syntax.

6. Semantics

Semantics focuses on meaning, the goal of reading. Students must learn not only to decode words but to understand them in context. Instruction in semantics includes vocabulary development, figurative language, and comprehension strategies.

Even early readers need enough word meaning knowledge to make sense of early texts. If a child can decode the word cod but has no idea that a cod is a fish, reading stops at pronunciation. Semantics ensures that decoding connects to understanding—turning sounds into meaningful language. Early grades semantics practices include:

- Reading rich read-alouds and teaching vocabulary deliberately

- Categorizing and sorting activities (animals vs. plants, tools vs. toys)

- Discussing multiple-meaning words and student friendly examples of each meaning in context

- Teaching synonyms and antonyms

- Building background knowledge before and during reading

- Asking “why,” “how,” and “what do you think” questions

- Using real-life examples and visuals to make meaning concrete

How the components work together: The principles of structured literacy

But what does it look like? The six components of structured literacy do not operate in isolation. They are integrated through the principles of structured literacy, the way instruction is designed and delivered. Each element should be taught explicitly, systematically, cumulatively, with on-going evaluation used to inform and differentiate instruction.

- Explicit Instruction: Teachers clearly model skills, explain why they matter, and guide students through practice. Explicit instruction may look like expressly teaching students the first sound in a word. For example, “The first sound in sad is /sss/. Everyone, say the first sound in sad, /sss/.” Explicit instruction may also include using graphic organizers to teach text structure, and writing a complete sentence with a subject, predicate, and ending punctuation.

- Systematic Instruction: Skills are introduced in a logical order—from simple to complex so students can connect new learning to prior knowledge. Systematic instruction may look like teaching high-frequency letter-sound correspondences, then blending sounds to form simple CVC (consonant-vowel-consonant) words, and finally introducing more complex patterns like digraphs (e.g., "sh," "th") or silent "e." Systematic instruction may also look like teaching roots, prefixes, and suffixes then applying the knowledge to understand new words.

- Cumulative Instruction: New content builds on previously taught skills, reinforcing earlier learning through review and application. An example of cumulative reading instruction includes word chaining, where students change one sound at a time in a word to create a new word. For example, starting with "bat," students can change the initial sound to form "cat," then "hat," and “sat.” Reinforcing phonics patterns by changing only one letter or sound at a time shows students how words are related.

- Diagnostic Instruction: Teachers continuously assess understanding and adapt lessons to meet each student’s needs. IDA states, “Content must be mastered to the degree of automaticity to free attention and cognitive resources for comprehension and oral expression.” Diagnostics include a host of formal and informal assessments that provide insight into a student’s reading growth and mastery over time.

Learning to read is complex. Structured literacy reminds us that the elements and components are integrated like vegetable soup and not just an assortment of ingredients on a plate. Phonological awareness feeds directly into phonics, which prepares students for decoding multisyllabic words. Morphology strengthens vocabulary, while syntax and semantics ensure that students comprehend what they read.

The broader impact: Why structured literacy matters

Structured literacy supports students in learning to read while reading to learn. By mastering foundational reading skills, students can access content across subjects, think critically, and express themselves in writing. Interdependence makes structured literacy an approach that honors both the teaching of each component individually and practice and application collectively.

When we apply science of reading research through structured literacy we’re building a lasting foundation for student success. The principles and components of structured literacy offer more than just strategies; they offer a promise that with the right instruction, every child can learn to read well. And when every child can read, every child can thrive.

***

Dive deeper into the science of teaching reading. Learn more about our science of reading curriculum, an evidence-based approach that builds on the components of the science of reading, plus integrates background knowledge and writing.