Incorporating meaningful writing practice into the middle school ELA classroom can be a challenge. I can still recall my students’ groans whenever I announced a writing activity! Even when students were excited to write, finding the time to work writing lessons into our already-packed ELA curriculum sometimes felt like an impossible task.

This list of fun and quick writing activities for middle school students can help! Aligned to the strands of Joan Sedita’s Writing Rope, they address the critical writing skills students need for high school and beyond, including critical thinking, syntax, text structure, and writing craft (see Sedita’s full model here).

Broken down into the genres of creative writing, narrative writing, argumentative writing, and informative writing, the activities can be done in 20 minutes or less, include differentiation strategies, and incorporate ideas for how to connect the writing to texts.

Reducing writing anxiety

Since writing can be intimidating for students, it’s important to create a low-stakes environment to get them started. Here are some quick and simple routines you can build into all your middle school writing activities to reduce stress:

- Set a short, clear time limit. Time-boxing writing activities keeps tasks manageable and focused. Ten minutes is a good starting point.

- Focus on completion, not perfection. Students’ goal within the writing time limit is to get their thoughts down, even if their draft is messy. When possible, allow time to revise their first draft work before asking them to share or turn it in.

- Copy a mentor text style. Use short, high-quality mentor texts as models and zero in on specific craft moves (such as a strong opening, smooth transitions, or effective dialogue). Then, have students imitate these strategies in their own writing.

- Build in a micro-share-out. After the timed writing, invite students to choose one sentence, phrase, or idea to share with a partner, small group, or whole class. This is a low-pressure approach and allows them to self-select their best ideas.

- Try a “one glow, one grow” routine. Incorporate a feedback approach of providing one positive comment (“glow”) followed by one suggestion for improvement (“grow”). Model this routine for students and have them use it in their feedback to one another.

Writing activities for middle schoolers

Creative writing activities

Reduce academic pressure and encourage hesitant writers with playful creative writing activities. Drawing from the foundational writing craft and syntax strands of the Writing Rope, these activities help students sharpen skills like imagery, voice, and sentence structure. Additionally, they can draw on their lived experiences and the content they’re studying to access and build knowledge.

Activity 1: Six-word story starter

This fun challenge has a low barrier to entry. Six-word stories are quick, fun, and perfect for building confidence before expanding into longer writing.

How it works: Students draft several six-word stories (e.g., “No GPS. Wrong turn. Best day.”). Then, pick one to expand into a 150-word story by adding elements of setting, conflict, and suspense.

How to differentiate:

- For multilingual learners: Pre-teach or review the meanings of “setting,” “conflict,” and “suspense.” Encourage brainstorming in student’s preferred language.

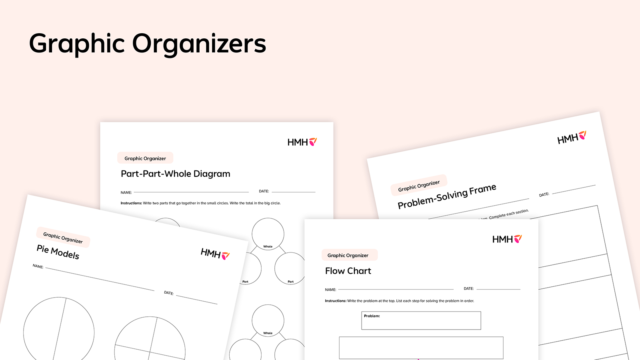

- For striving writers: Provide a graphic organizer where students can map out the key elements of setting, conflict, and suspense before they begin writing the longer story.

- For writers who need a challenge: Invite them to experiment with different ways to vary their sentence structure, such as using a dash for emphasis or inserting a participial phrase as a sentence opener.

Connect to text: Use an excerpt from a short story to demonstrate some of the story elements. For example, you could share the first two paragraphs of “The Tell-Tale Heart” by Edgar Allan Poe to showcase a strong voice, immediate tension, or how detail and depth can be packed into a short passage.

Activity 2: 100-word biography

Writing a concise biography helps students focus on strong word choice and organization while building knowledge about historical or literary figures.

How it works: Provide students with a list of literary or historical figures, and then ask them to write in two rounds. In the first round, they draft a 100-word biography about their chosen figure. In the second round, they revise using more descriptive or precise nouns and verbs.

How to differentiate:

- For multilingual learners: Allow them to make notes in their preferred language; provide a bank of relevant nouns and verbs.

- For striving writers: Provide sentence frames for topic and concluding sentences; scaffold chronological writing with a bank of transition phrases.

- For writers who need a challenge: Require that they use an appositive or absolute phrase to level up their sentence sophistication.

Connect to text: To build content knowledge and emphasize conciseness, provide a short author biography and have students distill the most significant points into an outline.

Narrative writing activities

Narrative writing activities are a great way to focus on the text structure strand of the Writing Rope. With these activities, students practice sequencing events, capturing cause and effect, and developing a sense of story structure.

Activity 3: Emoji memoirs

Practice “showing” instead of “telling” with a low-pressure, student-friendly way to tell personal stories and sequence events.

How it works: Drawing from a real-life moment, students choose 3–5 emoji to represent the sequence of events and their reactions and feelings to the events. Then, they expand it into a 150–200-word micro-memoir.

How to differentiate:

- For multilingual learners: Share a bank of temporal connectors (“first,” “then,” “finally”) or sentence starters to support sequencing.

- For striving writers: Provide a scene-building scaffold with sections for Action, Inner Thoughts, and Imagery/Sensory Details so they can organize their thoughts before writing.

- For writers who need a challenge: Require them to include a flashback.

Connect to text: Choose a short mentor text with a clear chronology, such as “The Necklace” by Guy de Maupassant, and have students plot the chronology on a timeline using emoji to represent each plot point.

Activity 4: “What if . . . ?” alternate ending

Writing an alternate ending to a mentor text encourages students to think critically about plot, character decisions, and theme.

How it works: Students use a mentor text to identify one character decision that, if changed, would alter the story’s outcome. Then, they draft the new ending, preserving the tone of the story.

How to differentiate:

- For multilingual learners: Provide students with a simple three-column chart to organize their thoughts featuring the following: Author’s Choice, My Choice, and New Ending. Allow them to fill out the chart in their preferred language and use it to inform their writing.

- For striving writers: Provide sentence frames to support planning: “Instead of ___________ , [character] decided to ___________ . This changed ___________ and instead led to [new outcome].”

- For writers who need a challenge: Encourage students to make a change that results in a surprise or cliffhanger ending.

Connect to text: Once students have completed their alternate ending, revisit the theme of the mentor text and have them analyze whether their ending changes or enhances the theme of the story.

Argumentative writing activities

Students’ ability to form opinions, make claims, and support them with evidence connects to the critical thinking and text structure strands of the Writing Rope. These short, structured practice activities prompt students to build and use knowledge from class texts and topics, weigh sources, choose evidence, and answer, “So what?”

Activity 5: Micro-argument: Claim in 100 words

Students practice making claims, supporting them with evidence, and explaining their reasoning, all in a bite-sized, manageable format.

How it works: Share an engaging opinion statement, such as “School cafeterias should serve breakfast all day” or “Gaming improves problem-solving skills,” and ask students to take a stance on the statement. Then, they’ll write a clear claim, add two pieces of evidence, and close with one “So what?” sentence that explains the relevance of their claim.

How to differentiate:

- For multilingual learners: Pre-teach or provide a bank of connector/transition phrases, such as “as a result,” “this means,” or “because of this.” You can also provide sentence frames to help them organize initial thoughts: “I agree/disagree that ___________ . One piece of evidence that proves this is ___________ . Another piece of evidence that proves this is ___________ . This is important because ___________ .”

- For striving writers: Provide a simple organizer with three sections (Claim, Evidence, and Why It Matters) that they can use to bullet their thoughts before writing.

- For writers who need a challenge: Ask them to add a counterclaim and rebuttal.

Connect to text: Following the short practice activity, choose an informative text on which students can develop a clear opinion. Have them complete the same activity using the text as their source, then expand their ideas into a longer piece of argumentative writing.

Activity 6: Evidence debate

Teach students to evaluate the credibility of different types of evidence with a fun writing exercise! Students will choose the best type of evidence to support a claim—and promote their choice in a persuasive pitch.

How it works: To introduce students to the varying credibility of different kinds of sources, share an engaging claim and a list of four types of sources. Students evaluate the credibility of each type of source. For example, if the claim is “Homework should be banned on weekends,” you might offer the following possible types of sources:

- A research study that supports the claim

- Results of a student or teacher survey

- A quote from a parent about how busy weekends are

- An online news article about homework

Students choose which type of evidence would be the most credible in supporting the claim. Then, they write a 100-word “pitch” that promotes their selected type of source—in this example, the research study—as the most effective.

How to differentiate:

- For multilingual learners and striving writers: Pre-teach or review the terms “evidence” and “credible,” and ensure students understand the meaning of the word “pitch” in this context. You can also provide sentence frames to get them started: “The best evidence to support the claim is ___________ because [reason 1], [reason 2], and [reason 3].”

- For writers who need a challenge: Require them to include the first and second best pieces of evidence in their pitch.

Connect to text: After the initial practice activity, students apply their evidence evaluation skills to an argumentative text. Students identify and evaluate the different pieces of evidence from the text, then repeat the pitch-writing activity.

Informative writing activities

Students build and use content knowledge most explicitly in informative writing: defining terms, explaining processes, and writing with an objective tone. These activities strengthen the text structure strand of the Writing Rope and encourage students to consider the audience and purpose of their writing.

Activity 7: Explain this!

Analyzing images and writing informational paragraphs helps students practice objective, precise writing.

How it works: Provide students with a compelling image and ask them to write an informational paragraph by breaking the paragraph down into four replicable components: a topic sentence (what the image shows), two factual observations about the image, and a context line that situates the facts in a larger context. Here’s a model of how this is broken down using a photo of Mars’ surface:

- Topic sentence: The image shows the surface of Mars.

- Observation #1: The ground is covered with red dust and rocks.

- Observation #2: A robotic arm is picking up samples of the dust and rocks.

- Context line: Studying the surface of Mars helps scientists understand the makeup of the planet.

How to differentiate:

- For multilingual learners: Allow notes in the student’s preferred language and scaffold the activity with a T-chart with the headings “What I See” and “What It Means.”

- For striving writers: Provide multiple model paragraph examples.

- For writers who need a challenge: Ask them to add a cause and effect or compare and contrast statement to their paragraph.

Connect to text: Have students identify the topic sentences, factual observations, and context lines in paragraphs from an informational reading text.

Activity 8: What’s the process?

Explaining a process helps students organize their thoughts, use sequence language, and communicate clearly.

How it works: Ask students to think of a process they complete every day, such as brushing their teeth, catching the bus, or feeding a pet. Then, they write a five-sentence explanation using sequence connectors and precise verbs.

How to differentiate:

- For multilingual learners: Provide a bank of transition words (“first,” “next,” “afterward,” etc.) and sentence frames (“The first thing I do when I ___________ is ___________ . The next step is ___________ .”).

- For striving writers: Scaffold by having students create a numbered list of steps to organize their thoughts before they begin drafting.

- For writers who need a challenge: Once students complete a draft, instruct them to examine every verb they’ve used and swap in more precise or vivid verbs.

Connect to text: Identify a “process” from a text the class is currently reading and ask students to complete the same activity. For example, if reading “Thank You, Ma’am” by Langston Hughes, you could ask students to write the process Mrs. Luella Bates Washington Jones uses to try to teach Roger to behave himself.

Conclusion

When writing activities for middle schoolers are short, structured, and a little bit playful, it lowers the barrier to writing, reduces anxiety, and allows for critical skill-building. Use these activities to develop your students’ writing skills, laddering up from smaller tasks to fuller drafts over time. You can have students keep a writing portfolio of these micro-activities and allow them to choose which ones they want to expand into full drafts in the future. As students practice across all four genres, they’ll gain confidence and competence in the writing skills they’ll need for success in high school.

***

Try Writable for Grades 3–12 to support your ELA curriculum, district benchmarks, and state standards. The program provides more than 1,000 customizable writing assignments and rubrics, plus AI-generated feedback and originality check that will save teachers time while boosting student skills.

Be the first to read the latest from Shaped.